Even 50 years since its first season began on 15th September 1971, Columbo remains a TV show like no other. The US series with Peter Falk in the title role – as the ramshackle, eccentric, cigar-chomping, raincoated LAPD homicide detective Lieutenant Columbo – revolutionised what a cop show could be. Here was a murder mystery where the murder was no mystery: audiences saw the deadly deed at the start of each episode, invariably carried out by one of LA's rich and famous in an attempt to preserve their esteemed reputation.

More like this:

- Nine shows to watch this Septemeber

- Why old TV shows are good for the soul

- A superb and starry detective thriller

It left the rest of the show not as a "whodunnit" in the vein of Agatha Christie, but a "howcatchem", with the unassuming, amiable yet sharp-witted Columbo working to unpick the killer's "perfect" alibi one seemingly insignificant clue at a time – shoelaces, caviar, air conditioning – before bringing down their arrogant conceit with a final piece of incriminating evidence in a thrilling "gotcha!" moment that Falk himself referred to as the "pop". Columbo's methods often involved elaborate set pieces where traps were set for the murderer (planting a false address of a suspect knowing the killer would try to frame him; asking a man to pretend to be his blind brother to break an alibi) that were dramatic, cathartic finales (even if the charges wouldn't always necessarily stand up in a court of law).

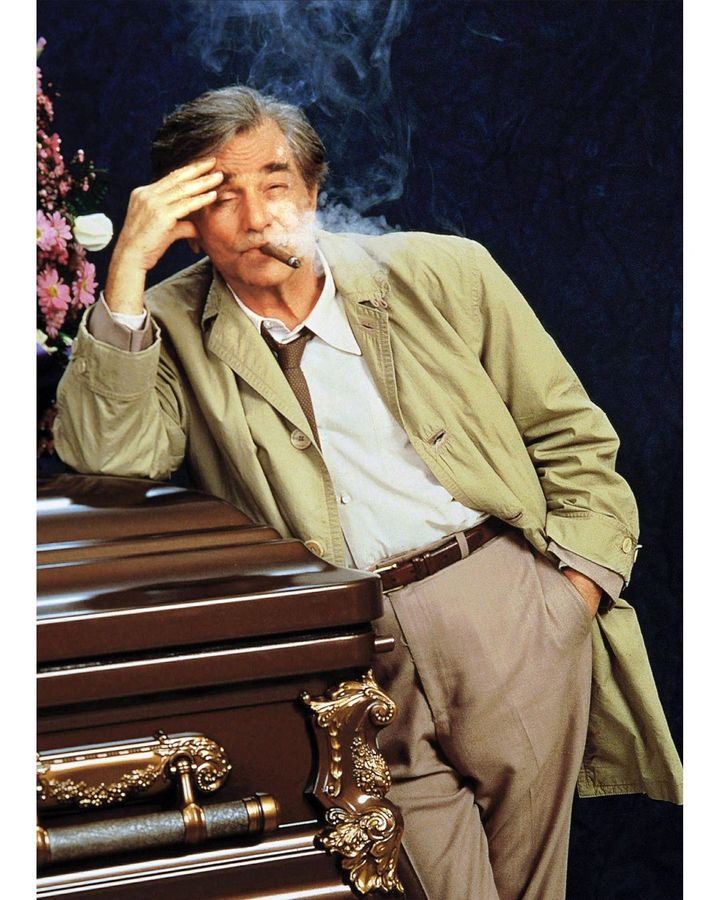

'Just one more thing,' was the detective's catchphrase – as he spotted the vital clue (Credit: Alamy)

On paper, it was a niche concept that even network executives doubted could work. But Columbo made a virtue of formula, and with intelligent, detailed scripts and a stellar performance from Falk, it became an unlikely worldwide phenomenon across eight series from 1971-1978, and then again sporadically from 1989-2003. The initial 70s run set a gold standard in event television, attracting grand guest stars to play the murderer (Gene Barry, Jack Cassidy, William Shatner, Anne Baxter) and emerging talent to shape its look and feel (Steven Spielberg and Jonathan Demme both directed episodes; writer Steven Bochco went on to create the hugely influential Hill Street Blues). It made a global star of Falk, who won four Emmys and a Golden Globe. The show was syndicated across 44 countries, resulting in some unusual tributes: there is a statue of Columbo in Budapest; in Romania, Columbo was so popular that when the show ended, the government asked Falk to video an address to the nation to confirm that it wasn't the regime's strict import restrictions that were responsible for the lack of new episodes.

"I truly believe that Columbo was a landmark in the entertainment industry," says Jack Horger, producer on the show between 1992 and 2003. "It flipped everything on its head," agrees David Koenig, author of a new book, Shooting Columbo: The Lives and Deaths of TV's Rumpled Detective. "Columbo wasn't really a cop show. It was a drawing or a mystery done backwards with a cop as the lead. It was an anti-cop show".

The history of the character of Lieutenant Columbo actually predates the TV show. Schoolfriends William Link and Richard Levinson, inspired by Porfiry Petrovich in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment and the books of GK Chesterton, had already used Lt Columbo on stage with Prescription Murder, a play influenced by the "inverted mystery" format used by Alfred Hitchcock in Dial M for Murder. Interested in the burgeoning TV movie scene of the late-60s, the pair took Prescription Murder to NBC. They had initially wanted Bing Crosby to play Lt Columbo, but after a semi-retired Crosby decided he preferred the golf course to the TV studio, it gave an opening to Falk who, having come across the script, contacted his casual acquaintances Levison and Link. "I'd kill to play that cop," Falk told them.

Despite reservations – at 39, Falk was much younger than they had envisioned for the part – it proved an inspired decision. Even if the pilot saw Falk play a sterner, straighter Columbo – the quirks and mannerisms hadn't yet been perfected – Prescription Murder was a huge hit. After Falk was eventually convinced to commit to a full series of Columbo, it premiered on NBC's Movie Mystery Week, in rotation with McCloud and McMillian & Wife. It immediately eclipsed both shows.

The irascible, amiable Lieutenant Columbo was played by Peter Falk, who became synonymous with the role (Credit: Getty Images)

It was clear from the outset that Lieutenant Columbo was the anthesis of a TV cop. He wasn't tall or macho; he didn't have a sidekick or squadron. He didn't carry a gun, and wasn't violent; he was squeamish at the sight of blood. In fact, aside from the occasional flashing of his badge – which showed to eagle-eyed fans that Columbo's never-revealed first name was in fact Frank – you'd barely notice he was a policeman at all: there were no shootouts or high-speed car chases, he was hardly seen in the office or at the police station. He didn't chase women – his devotion to his never-seen but constantly referenced-to wife Mrs Columbo, and the never-ending (no doubt exaggerated) stories about his extended family, presented a man of morals and virtue. "There was nobody or nothing like Columbo at all before him," Koenig says. "All the detectives were these hardboiled, emotionless, tough guys. And he was the opposite of that in every way. He hated guns and violence."

Instead, with distinctive posture, exaggerated hand gesticulations and a contrived forgetfulness – his habit of leaving a room, only to return having remembered "just one more thing" became his trademark – Columbo stumbled his way around LA's mansions with the dishevelled air of a confused gardener. Yet as Lee Grant tells him in the 1971 episode Ransom for a Dead Man, it was always the jugular he was after.

At any crime scene, he'd spot a little "detail" that bothered him – an out-of-place newspaper, a car-tyre track, a nightgown, an unsmoked cigarette – that would set his suspicions alight. Investigations into the murderer, always duped into inadvertently helping by Columbo's humble ways, were slow-building, cerebral, dialogue-based encounters that saw Columbo eventually wear the criminal down with a mixture of astute perception and dogged persistence: not so much death by a thousand cuts as mildly irritating prods on the arm. His unfailing politeness meant he often sympathised with the murderer, and in some cases even likes them (as he tells Ruth Gordon in 1978's Catch Me If You Can).

It was the humanity of Falk's performance that gave Columbo such a universal appeal. "One ought to take one's hat off to the extraordinary acting skills of Peter Falk," says broadcaster, actor and writer Stephen Fry, a Columbo connoisseur who believes it is the greatest television series of all time. "It's a beautiful, brilliant performance. He becomes the character, but he never loses the kind of technique that he learned with his fellow young actors with John Cassavetes. And I think anyone who's ever tried film or television acting will just bow their head at the sheer skill, the concealed artistry. He’s so natural. There's such a warmth to it".

Falk embraced the character to the point that where he ended and Lt Columbo started was increasingly difficult to ascertain. He wore his own clothes – a tatty old raincoat, a very 70s-coloured suit and tie – to give an appearance so shabby, Columbo is once mistaken for a homeless man in a soup kitchen. The comedy capers that provide such a light touch – the relationship with his dog, escapades in his beaten-up old Peugeot, the constant misplacing of items (pads, pencils, lighters, bags of evidence) – were as much a Falk trait as Columbo's.

"The thing that surprised me most about researching the book was how much Peter Falk was Columbo," Koenig says. "Almost everyone who knew him and worked with him loved him, because imagine hanging out with Columbo, how fun that would be? But also how infuriating he could be because, you know, just imagine hanging out with Columbo."

The series had a winning formula – the rumpled Columbo was always under-estimated by the rich and powerful suspect (Credit: Alamy)

"There were a lot of similarities. I'll have to admit that," Horger says. "He was technologically challenged. He had difficulty changing a light bulb. The fact he couldn't find the keys to his car and things like that, they're very characteristic of Columbo. He was kind of a bumbling guy. But you know that phrase, dumb like a fox? That was him. He was a pretty shrewd guy. And he was extremely good at (playing Columbo)." Falk's influence didn't stop at acting; he soon moulded the entire show in his image. The book Shooting Columbo explores how Falk, who in the 70s regularly threatened to quit in protest at pay and conditions, often re-wrote scripts and constantly ad-libbed scenes, insisting on dozens of takes to perfect Columbo's characteristics (the murderer's frustrations at Columbo were often genuine expressions of annoyance at Falk). He was soon even vetoing guest stars and attempting to control production. "By the second series, he was literally saying yes or no to everybody," Koenig says.

"Let me put it this way – he got what he wanted. Always," Horger says. "But over all those episodes over the decades, he had a pretty good feel for that part. Needless to say, he was usually right."

Cat-and-mouse game

One thing Falk rarely tampered with – in the 70s at least, aside from the divisive episode Last Salute to the Commodore – was the inverted mystery format that is essential to Columbo's appeal. It is an alien concept to modern audiences. Whereas series on streaming services often stretch out story arcs over as many episodes as is profitable, with a string of mini-cliff hangers, Columbo shoots its shot immediately: you see the killer, their backstory, motive and the deed itself within 20 minutes, before Columbo even arrives on screen. In theory, it should take the suspense out of the show in a heartbeat. Yet it sets in motion an absorbing psychological tussle, a series of intellectual mind games between Columbo and the killer that fascinates audiences.

"I think it's the pleasure of watching a cat go after a mouse," says Fry. "Seeing him work out the clever clues is so satisfying. And it puts us in a privileged position where we know what's happened. And although we should just say 'well of course we know, they've told us at the beginning', somehow we do feel superior. And we know that our champion Columbo is going to get his way. It's also the sheer pleasure that we know him and the villain doesn't. The villain underestimates him every time, and that moment of 'I may have underestimated you' is such a pleasing moment".

It's what made the writing all the more impressive: when the killer moment comes before the main star has even arrived, how do you keep people hooked? "It was doubly hard to write for," Koenig says, "trying to sustain interest and suspense when your biggest surprise was already unveiled. It was always a problem with Columbo finding writers who could write an hour and a half of two guys circling each other. How do you make that interesting? It was very, very hard to do."

Faye Dunaway was among the many high-profile actors who were cast in the series (Credit: Alamy)

For that to work, Levinson and Link constantly pitted this relatable everyman – who eats chilli at the local diner, drinks root beer and takes his wife bowling as a treat – up against LA's lavish aristocracy. Very rarely did Columbo face a foe from a similar social background: the fan favourite Swan Song, where Johnny Cash plays an exaggerated version of himself as a country-music star who kills his wife and backup singer, is the most notable example of social parity. Normally, Columbo is facing either the outlandishly famous (crime writers, actors, politicians) or moneyed, successful professionals (surgeons, psychologists, even his own crime commissioner).

It means Columbo is often apparently confused by the rarefied company he keeps: he doesn't know anything about classical music, or subliminal cuts, or chess, or wine, or photography (Mrs Columbo, on the other hand, is presented as a culture vulture, forever a fan of the killer's work). This ignorance on Columbo's part – often feigned, almost always affected – allows him to draw in the murderer with a cunning humility that belies his understanding of human behaviour and the criminal mind.

"I suppose I am a sophisticated, literate-type figure, so I'm more representative of the villains," says Fry. "But we love Columbo because it's the triumph of the shabby, ordinary working man, who is impressed by things that he considers classy. Not a university-educated kind of mind, but he has a wisdom and instinct, a tenacity, as well as a charm and pleasantness. He is a nice guy, a likeable guy. He's on the side of the angels".

This David v Goliath context is a key part of the show's appeal. The preening arrogance of Jack Cassidy, Robert Culp and Patrick McGoohan makes Columbo's eventual victory all the more satisfying. "There are some villains who are just vile and deserve to be caught," says Fry. "They're arrogant. They absolutely have it coming." Yet Koenig is nonetheless keen to point out that the concept of class warfare wasn't central to the creators' thinking. "I don't think that was intentional or conscious to make some sort of political statement. For them, it was dramatic device for this character. And I think people enjoy it better when this millionaire guy, who thinks he has no flaws, is being taken down a peg. I think people like that."

The initial run ended in 1978, with Falk and the network unable to agree on budgets. The show returned to much fanfare in 1989, although among some excellent episodes it was more inconsistent: murders and plotlines were sometimes far-fetched, while the show's straining for modernity (jazzy music, sex, violence) rather betrayed the serene effectiveness of the original run. As Falk got older, Columbo's character occasionally strayed from type, while the idiosyncrasies of his performance – the forgetfulness, the uncertainty – had less effect, because he was now acting his age. "He took a little more liberty," says Horger. "He wasn't just the little rumpled detective that that came along and stumbled on the clues. And there was a little more action, more sex in the in the later shows. But I think that was just not a reflection on Columbo. That was a reflection on society. We had moved a long way from the 70s".

Columbo has a global fanbase – a statue in Budapest, Hungary commemorates the character (Credit: Alamy)

After what proved to be the final outing, 2003's Columbo Likes the Nightlife, Falk planned one more Columbo episode, Columbo's Last Case (that would start at Columbo's retirement party). But a combination of lack of network interest and Falk's age and declining health meant it wasn't to be. Falk died in June 2011 from Alzheimer's at the age of 83. "We used to say the show would just 'Peter out', which is what happened," Horger says. "Because that wouldn't have been his last episode. There was always one more thing. He loved playing the character".

Just over 10 years on from Falk's death, Columbo has enjoyed a resurgence during the coronavirus pandemic, as it is not just remembered by those who loved it initially, but discovered by a new generation (Twitter is currently full of Columbo memes and posts). For a show that on the surface seems antiquated – "it just reeks 70s," Koenig laughs, "I mean, the hairstyles and the clothes and everything" – it has found an audience with younger people.

"I think why it became so doubly popular during the pandemic was because we were all locked in, and it takes people back to a simpler time," Koenig says. "You're part of this easier, more predictable, more understandable time where things don't change quite as quickly. And, it's a mystery in which you already know the answer, so it's comforting in that way."

A Columbo reboot, possibly staring Mark Ruffalo or Natasha Lyonne, has been much touted for years. "It's inevitable" Koenig says (although the ill-fated and borderline sacrilegious 1979 spinoff Mrs Columbo, starring Kate Mulgrew as Columbo's hitherto unseen wife, might give anyone pause for thought). Yet even if the character is resurrected, it is the original TV run, and Falk's iconic performance of Lieutenant Columbo, that will continue to keep audiences gripped.

"It's stood the test of time for 50-plus years now," Koenig says. "That character is still vibrant and alive, appealing to people. People love that central character, that basic format, that fact that it's not political, it's not violent, it's not all the things television shows are today, it’s something different. And that's its charm. That's what people love about it."

Love TV? Join BBC Culture’s TV fans on Facebook, a community for television fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"still" - Google News

September 10, 2021 at 06:04AM

https://ift.tt/2X3hra7

Why the world still loves 1970s detective show Columbo - BBC News

"still" - Google News

https://ift.tt/35pEmfO

https://ift.tt/2YsogAP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why the world still loves 1970s detective show Columbo - BBC News"

Post a Comment